If you prefer, you can listen to the audio version here.

It’s proven to be practically impossible to livestream a Mass Effect game and not have the ending come up at some point (usually several times) during a playthrough. I quite enjoy discussing the topic, but having answered the most common questions many times (“What do you think about the endings?”, “Which one do you choose?” etc.), I decided to collect my thoughts into a more organized, permanent form. That way I can easily point my viewers to it in case they are interested in knowing more but it isn’t feasible to talk about the ending at the time. As I got to work, I realized it was going to grow far beyond the scope I originally had in mind. I wanted to make sure I had my facts straight and that there wasn’t any lore or plot details I’d forgotten about, so merely reviewing important cutscenes, collecting materials and transcribing relevant dialogue took a fairly long time.

The original purpose of my project has remained the same throughout, however: I do not aim to label any of the endings as bad or good, nor to focus on my personal headcanon. I will present my “preferred” Crucible choice, but my main objective is to consider multiple angles and break down the components of the ending that I find interesting in general. This is thus a quest to expand my own knowledge while hopefully also providing additional insight and perspective to the reader. I’ll provide some reminders where appropriate, but you’ll get more out of the analysis if you have the plot in somewhat recent memory. Also, rather than focusing on technical or practical aspects of the ending scene, this discussion is very much from an in-universe viewpoint – that is, I won’t go into how well or poorly I think the last hour was designed from a gameplay perspective. Other players’ takes on the ending and story have naturally helped shaped my perception of them, so especially in analyzing the Crucible choices, I’ll address some opinions I’ve come across and explain why I agree or disagree with them.

Before getting started, there are a few points I’d like to bring up just to ensure we’re on the same page, and to illustrate what kind of mindset I tried to keep during the process of writing.

A theory of relativity

The premise that there is a time and place for each ending is more intriguing and sensible to me than assuming some “objectively best ending” can be found. Each of the offered choices essentially represents a major change to the state of the galaxy. The change further occurs as a result of a decision made by a particular Shepard with a particular history – who in turn is controlled by a player with particular beliefs and values. It seems many players consider the ideal ending within the context of the “ideal playthrough”, typically with a high amount of peaceful solutions and characters surviving, but I think it’s important to keep in mind how many possible states there are after everything that might or might not happen over the span of three games.

The player’s perception of Shepard’s ultimate goal

An important underlying factor is what the player considers a good and worthy conclusion to their personal Mass Effect story. Perhaps the player is attached to the main characters and mainly wants them to survive and live happily ever after? Maybe they firmly believe nothing justifies the Reapers’ existence and primarily want them gone? Or maybe they agree with the assumption of inevitable conflict between synthetics and organics and focus on seeking the best solution to it? From what I can tell, people experience especially the final scene with the Catalyst very differently, and there seem to be just about as many views of Shepard’s final task as there are players.

Shepard knowledge vs. player knowledge

If the player has done multiple playthroughs or found out about the endings in other ways, they have perspective that Shepard lacks – and knowledge of futures no Shepard can live to see. The additional element this brings into decision-making is whether the player makes their choice based on everything they know, or based on Shepard’s limited perspective. For example, you know that synthesis appears to be a success, but Shepard might be dubious and won’t be around to find out whether it actually worked out for the galaxy.

And one more thing…

The “indoctrination theory”

I thought it best to let the reader know where I stand so that no ideas borrowed from the so-called indoctrination theory (IT) are expected anywhere in the analysis. Never during my own playthroughs have I experienced that BioWare’s storytelling suggests I should suspect Shepard of being indoctrinated, and the various fan hypotheses I’ve come across have done nothing to convince me otherwise. While I naturally respect people’s headcanons, no elements of the IT are even remotely interesting, sensible, or plausible enough for me to consider incorporating them into mine. Thus, in my personal ending discussion, the IT has no place. (If you want to know more, sizesixteens says it better than I could.)

With that out of the way, at this point I hope we can agree that it would be better – or at least more interesting – to abandon the notion that some endings are absolutely bad and others absolutely good. I’ve generally tried to be transparent about what I’m basing my claims on, so if anything is unclear or you spot mistakes, please feel free to let me know. Some subjective speculation is necessarily going to factor in, but I’ll do my best to clearly mark the ideas that are possible only because nothing outright contradicts them – just like many, many other things in a fictional universe.

The Crucible, Citadel and Catalyst

Before moving on to the different ending scenarios, I’d like to briefly discuss a set of rather formidable constructs. When discussing the endings choices I regard them as they are shown to us, but in this section I’ll step a bit further into speculative territory. I’ll use either “Catalyst” or “Intelligence” depending on the context, but they generally refer to the same being.

The Catalyst

First of all, taking the Catalyst’s information at face value is by no means self-evident among many players I’ve talked to. In order to be in the same ballpark, however, we do need to assume that the Catalyst exists and is able to communicate with Shepard somehow. We’re never really given an in-game explanation for how this is achieved and why the chosen shape is a boy whose death we’ve witnessed, but we might not necessarily need one. In fact, we have multiple precedents for this type of thing: for instance, as evidenced in Project Overlord, even Cerberus and the geth have developed and used technology that lets an organic mind interface with a virtual world. Recall how the geth were able to control Shepard’s perception of the consensus by introducing familiar elements, like making the removal of the Reaper code “feel” like using a gun. With this in mind, the ability to select a person from Shepard’s mind and appear to them in that form seems perfectly conceivable. Just consider the Leviathans’, Protheans’ or even asari’s mental capabilities – it’s not inexplicable magic in this universe, it’s reality. And certainly something you can reasonably expect from the arguably most advanced being you ever encounter.

As for why the image of that particular boy was used, we can only guess. But wouldn’t it feel a tad strange if the Catalyst chose someone we know, like Hackett, Anderson, or even our love interest? Although the boy was a stranger to Shepard, his face became forever imprinted on Shepard’s mind as a symbol of loss and failure, so his image would probably have stood out when searching Shepard’s mind for suitable candidates. Be that as it may, the important point here is that minds can be accessed, and virtual or otherwise unreal environments can evidently serve as stages for real communication and events.

The Crucible and Citadel

The “choice chamber” and the Crucible

The combined design of the Crucible and Citadel has fascinated me since my first playthrough, and I’m still wondering which device stands for the actual effect of the blast. In other words, is the synthesizing/controlling/destructive component a part of the Crucible, or the (presumably Reaper-built) Citadel? Or both? What made me ponder this was primarily the Catalyst’s comment that the Crucible is “little more than a power source”, which doesn’t sound like it would include the ability to alter the framework of all DNA in a galaxy in the blink of an eye. A visual scan also suggests that the “choice chamber” is in fact not part of the Crucible, which can clearly be seen suspended above Shepard’s location. Considering the limitations of the video game as a storytelling medium and what kind of narrative style the Mass Effect saga uses (important facts are spoon-fed to the player rather than inferred and pieced together from obscure clues), these observations can be dismissed as insignificant, but it’s certainly interesting to speculate on the implications. Assuming the Intelligence itself designed the Citadel, its body, could it really have accounted for the possibility of being replaced or destroyed by someone else? And if the Reapers didn’t build it, who did? The Leviathan tells us that the Intelligence “directed the Reapers to create the mass relays”, but I’ve played with the idea that it was in fact the Leviathan who created the Citadel, in so far that it was the original physical residence of the Intelligence. Thus, the choice chamber could originally have been something else – like an interface between the Intelligence and organics – and would have been exploited for use together with the Crucible later on. Either way, it doesn’t seem very likely that some later party would have been able to construct a connection point for the Crucible without the Intelligence realizing or stopping it (recall how the keepers mysteriously maintain and revert changes to the Citadel), so it remains unclear who exactly is the most likely to have built the choice interfaces.

Regardless of who constructed what, once the Crucible is finally docked and the Catalyst is allowed to interface with it, two interesting things happen: the Catalyst itself is changed somehow, and the harvest ceases to be its preferred solution. The process unlocks the new possibilities, but the Catalyst interestingly claims it is unable to realize them. Additionally, if Shepard responds negatively to the prospect of replacing the Catalyst, it says it doesn’t look forward to it, but “would be forced to accept it.” This passiveness initially made me wonder whether it is actually prevented from interfering, by the Crucible’s very design. Based on Prothean VI Vendetta‘s data, the previous contributors considered the Citadel itself to be the Catalyst, technically only using the Citadel as an amplifier and coordinator of the energy distribution. We also learn from Vendetta that the Protheans (and possibly earlier civilizations) suspected that the Reapers themselves are governed by some higher power, but it seems unlikely that they understood that this power was actually an AI residing in the Citadel itself. All the secrecy surrounding the construction and details of the Crucible in turn prevented the Intelligence from becoming aware of its existence and potential, right until they were successfully interconnected for the first time. Thus, it doesn’t seem likely that the Intelligence was knowingly prevented from interfering with the process. It either chooses to defer to the judgement of the “chosen organic”, or some other mechanic prevents it from overriding actions associated with the Crucible.

The terminology can also be a little confusing especially to a first-time player. When Shepard remarks they thought the Citadel was the Catalyst, the boy-shape clearly states that “the Catalyst” – the missing component – is not the Citadel, but indeed the Intelligence itself. Surely the Citadel still fulfills the technical functions as specified by Vendetta? How could the AI be the missing component if the designers of the Crucible weren’t even aware of its existence? These designations might seem odd, but it could simply mean that the Intelligence is inseparable from what we think of as the Citadel. That is, the physical space station could not interface with the Crucible in the intended way were it not for the hidden resident AI. This makes a good deal of sense – the Intelligence does say “the Citadel is part of me”, and we know that many of the station’s functions have been impossible to study and get to the bottom of, but they’ve simply been too useful not to utilize. (Recall how the Citadel was designed to “lure in” advanced races only so they could be easily ambushed at the start of the harvest.) Thus, the Citadel’s secrets can easily be attributed to the Intelligence, and the components needed for the Crucible could rely on them somehow. As far as we know the current cycle hasn’t even cracked mass relay technology, so it’s not surprising that the Citadel houses functions we haven’t been remotely aware of. Past cycles have been ahead of us in this regard (as evidenced by the Protheans’ Conduit, for instance), which might be one of the reasons the current scientists working on the Crucible didn’t fully grasp what they were dealing with.

As for which device stands for which effect, I do consider it plausible that the Crucible itself would include a mechanism that assumes control of the Reapers, in addition to providing enough destructive energy to wipe them out. Even our cycle managed to find a means to control Reaper forces using their own technology by studying it enough, so it seems perfectly possible that the concept could have been incorporated into the Crucible design, in a more advanced fashion on a much larger scale. An idea I’ve played around with is that synthesis, on the other hand, is the Catalyst’s own little addition. When Shepard asks why synthesis hasn’t been done sooner, the Catalyst reveals that “a similar solution” has been tried in the past, but that is has always failed due to organics not being “ready.” Since it also mentions that the Crucible is “adaptive” in its design, I certainly don’t think it impossible that the Catalyst itself would find a way to configure the Crucible to support this option.

The last few paragraphs constitute a fair amount of speculation on my part, the main point being that while the mechanics of the Crucible and Citadel raise some interesting questions, they can be plausibly explained within the universe. As is often the case with video games, it’s pretty easy to end up reading too much into things – especially when some of the details are oversights rather than intentional narrative clues – but it’s kind of irresistible to use your imagination to fill in the gaps of an epic saga like this one.

On to the meat of the analysis, then.

Refusal

Refusing to activate the Crucible is arguably the most straightforward choice regarding the immediate implications for the current cycle. It is repeatedly made clear that the Reapers cannot be defeated by conventional means, and, as we have seen, the Catalyst claims it’s unable or unwilling to end the harvest if the Crucible is not utilized as part of the new solution. But when the only alternative is death for everyone they’ve fought for and alongside, can there really be a scenario that’s even worse?

Shepard isn’t necessarily satisfied with the assortment of choices

For refusal to make sense with respect to continuity, we must assume Shepard had a change of heart sometime after the scene with the Illusive Man and Anderson. Everyone had agreed docking and activating the Crucible was the galaxy’s only chance, and Shepard knowingly used their last bits of strength to open the Citadel arms to make this very thing possible. One could always attribute the refusal choice to a heated moment of irrational defiance or resignation, but assuming Shepard hadn’t more or less lost their mind, the encounter with the Catalyst must have convinced Shepard that using the Crucible could result in something worse than death. Depending on whether the Collector base was destroyed or preserved, destroying or controlling the Reapers is the only option available if the Effective Military Strength is low enough. Could perishing quickly be preferable if Shepard’s only option is to destroy all technology and cause at least one more genocide? Or if Shepard’s only light at the end of the tunnel is the prospect of wiping the Reapers out of existence, but the Crucible can only be used to seize control of them?

I’ve considered the possibility that Shepard simply gives up at the end and deliberately leaves it to the next cycle to try and put things right, but it fits poorly with Shepard’s character. Even if important leaders have perished and the current cycle is held together by little more than feeble, temporary alliances, Shepard is pretty much scripted to fight to the bitter end. However, Shepard is not necessarily scripted to believe the Catalyst’s information, and certainly has the option to act contrary to its advice: maybe the Crucible and Catalyst seem like a vicious trap regardless of choices presented, and Shepard doesn’t want to risk making a grave mistake that can’t be undone. Even if everything was “done right” and the military strength is very high, nothing stops Shepard from considering the Catalyst a final Reaper trick that they must avoid falling for. Especially if the Commander absolutely resents everything about the Reapers and refuses to abide a single thing the Catalyst says, it doesn’t seem unthinkable that Shepard would rather cling to the hope that this cycle will somehow defeat the Reapers conventionally than trust its information.

Once the choice is made, Shepard’s final words mostly indicate that since they couldn’t end this on their own terms (whatever those might be), they won’t use the Crucible at all. The principle of free will is mentioned, but it doesn’t bear very close scrutiny: the Commander does have the freedom to make a choice on behalf of everybody else, whereas submitting to death and harvest probably isn’t something most would willingly do. Either way, it should be pointed out that just because an option isn’t easily the right one, it doesn’t have to mean it shouldn’t be there. There are, after all, other decisions in the trilogy almost unanimously regarded as poor or foolish in most circumstances, so its presence if justified even if the player considers it a terrible choice all around.

Once the choice is made, Shepard’s final words mostly indicate that since they couldn’t end this on their own terms (whatever those might be), they won’t use the Crucible at all. The principle of free will is mentioned, but it doesn’t bear very close scrutiny: the Commander does have the freedom to make a choice on behalf of everybody else, whereas submitting to death and harvest probably isn’t something most would willingly do. Either way, it should be pointed out that just because an option isn’t easily the right one, it doesn’t have to mean it shouldn’t be there. There are, after all, other decisions in the trilogy almost unanimously regarded as poor or foolish in most circumstances, so its presence if justified even if the player considers it a terrible choice all around.

In summary, while certain death is not easily the most fulfilling conclusion to a story that has to a great extent been about survival, refusing the options presented by a potentially deceptive figure can still constitute the final stand of a certain type of (sane) Shepard.

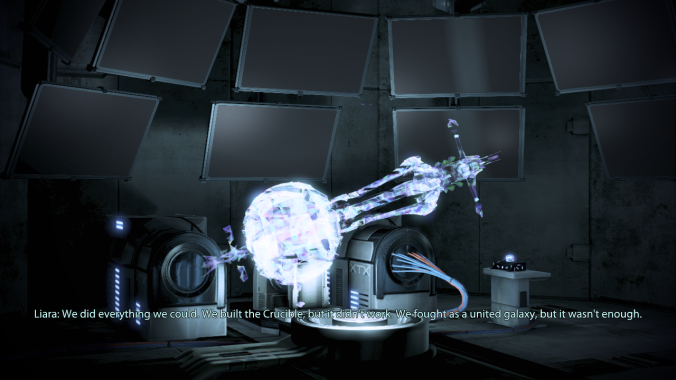

Liara’s capsule indicating that the races of our cycle perished

Synthesis

Every once in awhile I hear it claimed that synthesis is intended to be the “best choice”, or even “BioWare’s favorite choice.” Yes, the Catalyst explicitly states that is “the ideal solution” – inevitable, even – but as we have seen, Shepard doesn’t necessarily have to agree that the Catalyst knows best. The Commander can indicate that the Catalyst doesn’t understand organic life, but I don’t necessarily agree with that. The Catalyst knows that life definitely wants to exist – hell, the Catalyst itself wants life to exist – but based on its experiments and data, life is self-destructive if left alone. I don’t care what you want – you’re a danger to yourself and others, so get out of the way and make yourself useful until I get this synthesis thing working. Either way, it makes perfect sense that the Catalyst should favor this solution, as it’s the only one which guarantees that the problem it was created to solve goes away.

An argument against synthesis is whether solving this problem is relevant enough, so to speak. That is, just because you remove one source of conflict, why should it mean others won’t arise sooner or later? Haven’t organics also fought each other, even within a single race (such as the turian Unification War)? To be fair, I think this is a problem that player imagination takes care of rather easily. The Catalyst is supposed to have studied the rise and fall of civilizations long enough to figure out the main threat; it might only be concerned with the one type of conflict that constitutes a danger to all life, leaving “lesser” problems that can presumably be overcome without its intervention out of the equation. I often hear it claimed that making peace with the geth somehow disproves the Catalyst’s assumption of conflict, but it’s hardly that cut and dried. The ceasefire was only achieved under very specific circumstances after the harvest had already begun, and the Catalyst merely predicts that at some point the synthetics will gain overwhelming strength again – if not the geth, then some other machine race.  What’s more, among all interspecies relations data the Catalyst has ever collected, it’s not difficult to see one instance of peace drowning among other (worse) results. Along with other insights into the previous cycle, Javik describes how the Protheans’ very model of government was based on the need to unite all organics to stand against the threat of the machines. One can always argue that the current set of races can uniquely overcome this threat even without synthesis, but as an issue of past cycles, it can’t be dismissed – nor can the Catalyst’s thesis be objectively falsified.

What’s more, among all interspecies relations data the Catalyst has ever collected, it’s not difficult to see one instance of peace drowning among other (worse) results. Along with other insights into the previous cycle, Javik describes how the Protheans’ very model of government was based on the need to unite all organics to stand against the threat of the machines. One can always argue that the current set of races can uniquely overcome this threat even without synthesis, but as an issue of past cycles, it can’t be dismissed – nor can the Catalyst’s thesis be objectively falsified.

Back to how synthesis is supposed to unify all life and prevent fighting: at one extreme, conflict in general can be seen as a symptom of our as yet incomplete existence, and synthesis would allow everyone to understand one another well enough that no division or discord can occur in the first place. It is, of course, also possible to view synthesis as something far less intrusive; something that doesn’t alter us too much, but merely provides better grounds for getting along. Interestingly, judging by what Legion has told us, the “understanding” synthesis would bring to synthetics sounds like something the geth would not mind at all. They were quick enough to accept foreign technology in the face of extinction, and they have willingly studied organics in an effort to – that’s right – understand them. Recall that Legion itself was created to this end, with traits specifically designed for smoother interaction with organics.

No matter what exactly synthesis accomplishes, though, Shepard is doubtful about whether this is a decision one person should make on behalf of an entire galaxy. Then again, any verdict Shepard makes at this point has to be made on behalf of everyone else; as we well know, there is no time to whip up a poll and let democracy decide. Depending on your political or philosophical views, though, this might conversely be a decision that should not be based on a majority vote at all. No one will necessarily ever know that there even were multiple choices available – just synthesis or death. As a common citizen of the Milky Way, can’t an attempt to seize control of the Reapers or a massively destructive blast seem much more risky and terrifying than simply “integrating fully with synthetic technology”?

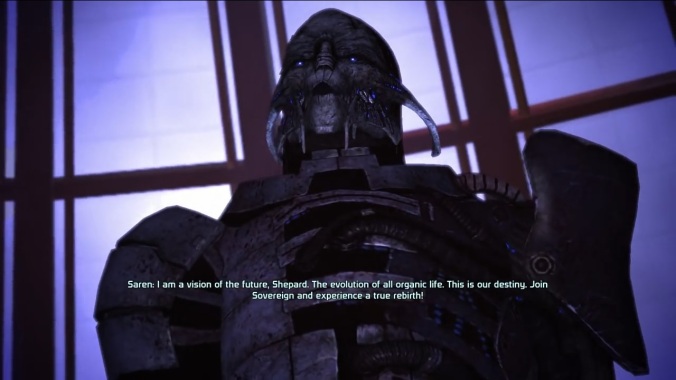

As a final point of interest, Saren Arterius has some dialogue relating to this concept. He claims to be a vision of the future: “a union of flesh and steel. The strengths of both, the weaknesses of neither.” As we will see with control later on, it’s one of the choices that are exposed to the player relatively early, but dismissed even within the game as mere ramblings of a crazy, Reaper-controlled villain. I think it’s unlikely that the Crucible endings had been thought of at the time the original Mass Effect’s ending was written, but it still fits in rather nicely. Since unifying organic and synthetic life is what the Intelligence has been aiming for all along, the idea could have been passed to Saren after he fell under Reaper control – even if the kind of “ascension” he underwent didn’t represent the Catalyst’s idea of synthesis at all.

While it can be difficult to quickly adjust to the notion that the Reapers don’t have to be the enemy, synthesis is no doubt a satisfactory solution for a Shepard who sees the forest for the trees and is willing to adopt unprecedented methods in their quest for galaxy-wide peace.

Destruction

One thing I find intriguing about the Catalyst is that it is unwilling (or unable) to simply shut the Reapers down or direct them to cease the harvest unless Shepard elects the destructive path for all things synthetic. There’s nothing that suggests the Catalyst isn’t actually in control of the Reapers, so we’re left to assume it’s simply not giving up that easily. In hindsight we know that it truly leaves the choice to Shepard: presumably it could just avoid mentioning the destruction option, or try to deceive Shepard in some other way, but it evidently doesn’t.

An advantage destruction has over the other Crucible options is that it does one of the things everyone hoped it would: it kills Reapers. The other options are only known to a limited extent and among smaller circles. The concept of controlling the Reapers has come up but been dismissed as the fantasy of an indoctrinated maniac. Shepard may learn of the synthetic-organic conflict through Javik and the Leviathan, but the public is likely oblivious to it. Yet, a destructionist might feel that even if you could eliminate the threatening factor of the Reapers, their existence simply isn’t justified: They’re based on sentient creatures harvested against their will, they have immeasurable amounts of blood on their hands, they are far more powerful than any other technology in existence… The reasons for why one might not want to keep them around are many. But as we know, it is not without a catch: there is no option to simply delete the Reapers and continue as you were, but you also have to account for technology and synthetic life being eradicated or damaged.

Some argue destruction doesn’t make sense for a Shepard who sided with the geth or is generally accepting of synthetic life. I’d say this is only really the case where the player has all the answers already and wants optimal outcomes throughout. Shepard can’t predict the future and has no way of knowing that sacrificing the geth, EDI and other AIs might prove an unfortunate necessity in the end. Although the writing mostly indicates Shepard is genuinely invested in peaceful coexistence, a more renegade approach could allow Shepard to only consider synthetics temporary allies until the Reapers have been defeated, in which case the point is also moot. The geth fought the quarians rather than died at their hands, but one can theorize that if they agreed to fight the Reapers, they would willingly sacrifice themselves so the other races could survive. (Personally, I’m not too sure about that. Both heretics and true geth have more or less allied with Reapers rather than faced the threat of extinction – if anything, they’ve shown that they want to live.) Given that AIs are still widely illegal and all geth were considered enemies until very recently, one can also argue that the sacrifice of synthetic life in particular is a loss that many other galactic citizens could probably live with.

Finally, destruction can very well make sense even if Shepard trusts the Catalyst regarding the synthetic-organic conflict. Successfully deploying a game-changing device can be seen as evidence that the Reapers’ strength has been matched and that they are no longer needed as preservers of life. If the situations with the krogan and geth were resolved peacefully, it might further strengthen Shepard’s belief that this cycle’s civilizations have overcome the problem the Intelligence was meant to solve by their own merit.

And, again, if Shepard feels the Reapers must die no matter what, it’s even simpler.

Control

Seizing control of the Reapers seems to be generally regarded as the least disruptive option to the peoples of the galaxy at large: no one has to get harvested, die in a destructive blast, or have their DNA forever altered. No technology except the mass relays is destroyed and our protagonist gains the ability to direct the Reapers as they see fit. So what are the downsides?

To some the mere process of assuming control seems far too sketchy; what if something goes wrong and Shepard just transforms into an “Intelligence 2.0”? Or worse? The way I see it, however, that concern applies to all three Crucible choices. That is, even if Shepard means to use the Crucible for destruction or synthesis, they must take the Catalyst’s word for how exactly it’s going to work. (And if Shepard doesn’t trust the Catalyst on this, it’s an even bigger risk.) This is the main reason I don’t consider any one option “safer” than any other – additionally, meddling with everyone’s DNA or disrupting the technology of an unsuspecting galaxy in the middle of a war seems anything but safe to me.

Risk aside, some seem puzzled by the idea of Shepard transforming into some virtual form. While not unheard-of in sci-fi at large, “uploading” an organic mind in such a manner that the self is retained might seem like a strange concept to Mass Effect players. Hidden somewhat deep in the lore, however, there are records of a curious civilization: in the face of extinction, the members of a certain alien race once abandoned their physical form as a people, instead transferring their minds into a virtual world housed in super computers aboard a spaceship and continuing their life and society there. (The story of this civilization, dubbed “Virtual Aliens” by the wiki, was told in a series of Cerberus News Network in-universe news articles.) We also know that the Protheans were capable of basing a VI on a person, giving them certain personality imprints, although we can’t be sure to which extent (if any) the original person “lives on” in virtual form. With at least one precedent within the universe, however, perhaps the notion of this kind of existence doesn’t seem as foreign.

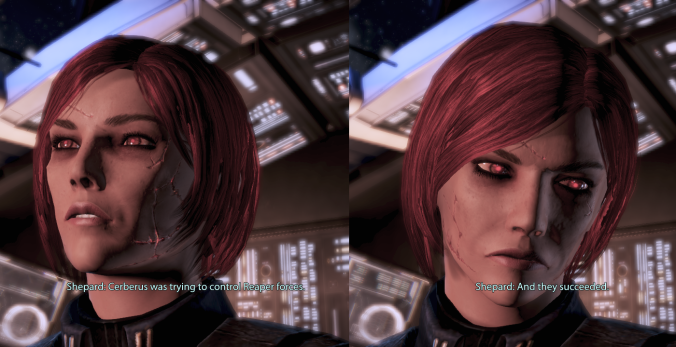

Moving on to contrasting control with the other options, one might argue that people do not necessarily expect or want the Reapers to be controlled. It is certainly true that the idea is portrayed in a negative light throughout Mass Effect 3, to the extent that it becomes “tainted” in a way many players probably can’t overcome. The Illusive Man shares his belief that the Reapers can be controlled almost immediately after the initial invasion, eagerly acclaiming it a means to securing human dominance (which Shepard naturally denounces). Shepard may bring the possibility of control up with Admiral Hackett, who simply retorts that the Illusive Man is wrong, insane, and so forth. Other close allies – such Anderson, Joker, and Garrus – also dismiss Cerberus’ doings as pure lunacy. But what does Shepard think? While the player naturally projects their own sentiments onto Shepard, based on the writing alone the Commander is not necessarily as convinced. When talking to Joker after the Sanctuary mission, for instance, Shepard may appear tentatively impressed with Cerberus’ experiments and acknowledge their success. Hackett “doesn’t care what [The Illusive Man] thinks he’s proven”, but is convinced that attempting to control the Reapers will only result in death and certainly isn’t something the Illusive Man should be trusted with. Outwardly, Shepard remains silent and doesn’t really take a stance on Hackett’s or other allies’ assertions.

As we know, the Illusive Man eventually turned out to be right, but nobody on “the good side” could foresee that one of their own could be given this opportunity. Put simply: if controlling the Reapers is seen as a powerful tool of sorts, the Illusive Man argues that he can and will use it; Shepard’s allies argue that it can not be used and don’t offer their opinions on whether someone else should use it; Shepard themself remains largely neutral on the subject, and once they learn that the tool can be used, they must decide whether to be the one to use it. This intriguing dilemma alone makes me rather fond of this ending choice in particular – it’s a very hot topic that’s been bounced back and forth throughout the game, and we finally have a chance to tip the scales one way or another.

Once a decision is made, as a player it is natural to be interested in what happens next. The narrated cutscenes provide some hints, but what the galactic scene will look like many, many generations later is of course left to the imagination of the player. The synthesis future largely depends on what the player imagines the effects of synthesis to be: Will everyone truly be immortal? Can they still get in conflict over things? What happens to those who didn’t want this transformation, or is that resistance eliminated in the process itself? As for destruction, even the highest-EMS future looks grim at first, but the Reapers are gone and technology will eventually recover. But what happens when the Reaper War doesn’t exist in living memory anymore? Will the synthetic-organic conflict eventually threaten all life in the future, too? The questions surrounding control are also quite intriguing: How will people regard the Reapers’ presence? To what extent will the civilizations be able to communicate with Shepard? What is their co-operation going to be like? What happens if they disagree? If the powers of the galaxy asked Shepard and the Reapers to leave them alone, would they? I’ve even played with the thought of outsmarting destruction in this regard: couldn’t Shepard wish to destroy the Reapers, but instead of causing all that unnecessary damage assume control of them and triumphantly lead them into the nearest black hole? These questions naturally don’t have clear-cut answers, and they might not be addressed in future installments. While one can endlessly speculate on various long-term consequences, they are almost completely under the control of player imagination. And it is, of course, up to the player whether Shepard’s choice should be based on detailed visions of the future in the first place.

Back to the topic at hand: Being the only ending narrated by Shepard, control is unique in the sense that it is colored by the Commander’s moral alignment. Where a Renegade speaks of fighting and defending, a Paragon speaks of sacrifice and sustenance. The “one for all” mentality is strongly present in both versions, making it similar to synthesis in this regard. Some consider Shepard’s implied survival a point in favor of destruction, but it’s hardly that cut and dried for everyone. It’s unsurprising that many feel Shepard “deserves” a happy ending which involves going on living together with the people that mattered to them, but for others, the survival of the main character per se is not as crucial. Instead of having their protagonist defeat the enemy and live to tell the tale, one might value altruism – becoming a legend not only because of great deeds, but also because of great sacrifice. I’m not implying any decision to destroy is essentially about saving your own skin, but I’m sure it matters to players who enjoy plausibly imagining that life goes on for their beloved characters. As I mentioned at the very beginning of the analysis, I’ve found that people have very different ideas of how Shepard’s ultimate goal comes into play and what it even is – in the end I believe these ideas are a pretty good representation of our narrative preferences and life values put together.

As if my bias has not already become evident, I will go ahead and say that I do consider control the most intriguing and satisfying ending of the bunch. In my story, Shepard set out to end the Reaper War even if it was going to claim their life – a possibility that’s hinted at several times during the game – and the Paragon ending narration resonates perfectly with my idea of a magnificent protagonist. I, too, first felt reluctant about giving the late Mr. Indoctrinated Madman kudos for having been sort of right all along, but it still represents a rather exhilarating twist. Control, but not like we thought. Ascension, but not like we thought. Another aspect that appeals to me is how Shepard’s connection to their kind will, in a sense, very much be preserved: I think there’s something very sad and very beautiful about this eternal mind, based on a living, feeling being, forever carrying the memories of its loved ones with it.

Many no doubt relish the feeling of doing what they set out to do back in the original Mass Effect, but if someone told me, “at the end if this trilogy you will destroy the Reapers”, I would’ve replied, “Alright, cool. As expected, then.” (Disclaimer: I’d have been devastated if any aspect of the ending had been spoiled to me beforehand.) If, on the other hand, I’d been told I’d ascend into a super-being that commands the Reapers, my mind would probably have been blown to bits. Therefore I’d say my favorite ending is based more on what I appreciate about a story than what I imagine I’d do in Shepard’s stead. I’m not sure the peace will last forever even in my own headcanon, but we’re not making real decisions in a real world – we’re wrapping up a story that we all have our own very unique take on.

And in my mind control is simply the coolest ending to the coolest story. Ever.

Conclusion

The discussion the Mass Effect 3 ending continues to fuel even after four years is no doubt an indicator of its complexity. I can understand that many felt more invested in the characters than the Reaper conflict and wanted the ending to reflect this, but I can’t agree with the popular opinion that your choices don’t matter, or that there is no choice at all. Sadly the rant-like negative reviews vastly outnumber the more reflective, dispassionate breakdowns (and make them hard to even find), but I hope my analysis provides some food for thought regardless of how you feel about the ending yourself. The story of the Mass Effect saga has been on my mind ever since I finished it for the first time almost three years ago, which I hope this project reflects. Thanks for reading it, and please feel welcome to check out my Twitch channel if you want to discuss or hear more.

Keelah se’lai! We anticipate the exchange of data. And… I should go.

Interesting commentary on Mass Effect, assuming of course that all three main endings can are assumed to have a ‘good’ result which will neutralise the Reaper threat.

Firstly, I am glad to discounted the Indoctrination Theory. I always disliked this theory and always rejected it.

I actually think that Control is the most straight forward ending, at least in the short term. Shep takes control and imposes peace on the Galaxy. This has an appeal to it, assuming Shep’s influence is benign. The problem is what happens far in the future after all Shep’s friends are long dead. How will Shep deal with an evolving Galactic civilisation he/she no longer relates to or understands? How will Shep’s immortality affect his/her personality and humanity? Very difficult to know.

Nothing much to say about Destroy beyond what you have said. Any Shep choosing this option assumes that the reapers are too dangerous and must be eliminated. The Shep will also either no regard synthetics as worth sparing, or regard their demise as a necessary sacrifice.

The problem with Synthesis is that Shep doesn’t know what it means. Even assuming that the effects are genuinely intended to be benign, it is so difficult to know how it will affect civilisation and and evolution. And how can we be sure the Catayst’s judgement is sound on this? Synthesis feels like a major gamble.

I find the Refuse option interesting. If we assume that Shep escapes the Citadel, it is actually the one option where Shep can feasibly survive and stay with his friends. I can just imagine Shep and co resisting the Reapers for decades, perhaps discovering new ways to fight and destroy them. In this case, the end of ME3 is just really the beginning of a new stage in the adventure.

I feel that all endings except for Synthesis are valid for me. It just raises too many questions, both philosophical and practical, as to how it would work. I think Synthesis is supposed to be the Utopian option. But that in itself is not satisfactory.

The other three options feel practically possible and the short term consequences can be imagined. None truly solves the potential for conflict. But then, for any form if life to evolve, there must be change and conflict.

LikeLiked by 1 person